From Poverty to Prosperity (and Back Again)

- Lydia Seaton

- Jul 2

- 6 min read

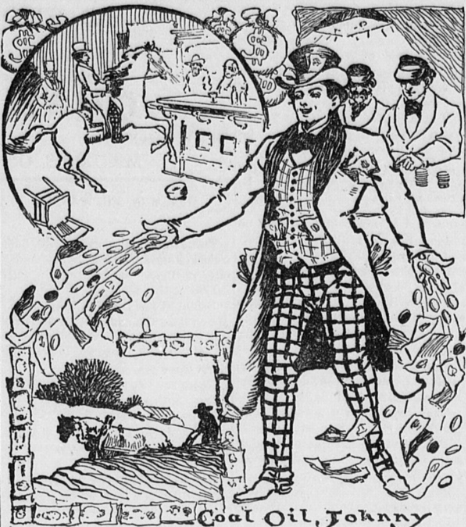

In the last few blogs, our staff have talked about all sorts of notable, infamous, and ethically complex characters from the Oil Region’s history (we’re looking at you, Ben Hogan). This week, our staff wanted to talk about a man who became an allegory for those that got rich in the oil boom… and subsequently became un-rich after the oil dried up… Coal Oil Johnny lived a life of luxury and prestige when the wells on McClintock farm struck black gold. However, the “black magic” became apparent a year later when he lost everything.

For more information on "Oil: Black Gold or Black Magic," visit the Venango Museum Tuesday-Saturday, 10:00-4:00!

J.W. Steele - Humble Beginnings

John Washington Steele was born in 1843 in Sheakleyville, PA in Mercer County. He and his older sister, Permelia, were adopted by Culbertson and Sarah “Sally” McClintock as young children. It was said that the couple took the children out of the “poorhouse” and brought them to their Venango County farm, where they were relatively well-off. The family lived along the Oil Creek just north of modern Rouseville. John – who would one day grow into Coal Oil Johnny – had a normal, pleasant childhood with his family. He passed his time with “hunting, fishing, and farm chores.” John's older sister, Permelia, died in 1851 from unknown causes. This loss was followed by his father, Culbertson, in 1855. Upon Culbertson’s death, he left the farm to his wife Sally.

In 1859 when Edwin Drake’s well successfully hit oil, speculators appeared in the county searching for promising spots to dig wells. One such spot was the McClintock property. Sally began leasing lots on the 200 acre property in exchange for oil royalties, and thus began the growth of her family’s wealth. John began working as a teamster on the family’s land and would haul barrels of oil to shipping points. He also would bring drilling materials to well sites. He learned to work with a great deal of the oil machinery, even helping to pilot the flatboats which transported oil down Oil Creek to the Allegheny River. In 1862, John married Eleanor Moffitt and the couple had a son together named Oscar.

In 1864, Sally passed away unexpectedly from burns she sustained in a house fire. The farm, the home, and all oil royalties were left to John.

Get Rich Quick (Get Broke Quicker)

In 1864, Eleanor became ill with an unknown disease. John, Eleanor, and Oscar then left for Philadelphia in hopes of getting better medical treatment and a change of scenery. From the death of his mother, John inherited $24,500. He also earned approximately $2,8000 from the oil royalties per day. The wealth he was quickly amassing was new to John, and it was at this point that he earned him the moniker of “Coal Oil Johnny” – a man who was a great spender, and an even better squanderer. He bought a custom carriage, fancy clothing, cigars, alcohol, jewelry, watches, and more during this period. He was said to have lit cigars with $100 bills – although this is believed to be more folklore than truth.

Coal Oil Johnny didn’t lose any of his money to “gambling” or “expensive real estate” – at a rate of around $3,000 per day, Coal Oil Johnny simply spent it. One story alleges that on a night out in Pittsburgh, John heard a performer sing a song he particularly enjoyed. John “stepped out from a box, handed the fellow a $1,000 bill and said, “Sing that again, will you? I like it.” A few days after this run in with the singer, John crossed paths with another man who was asking for “just one day’s pay.” The man – a gambler down on his luck – was given $3,000 by John. In response, the “fellow almost dropped dead.”

John also made the acquaintance of a man named Seth Slocum, who offered to act as his guide for a small fee. Seth was given free access to all of John’s money via a power of attorney. Together, the pair would go on lavish spending sprees, visit a tailor to order “gaudy” custom made clothing, purchase “diamond pins, gold headed canes, and they lived expensively and wild.”

John was convinced his wealth was only increasing, and would only ever increase, so his spending never slowed. He would enter saloons with a crowd of “friends” following him. John would order champagne by the basket, at one point ordering “all the champagne [they] can drink from [their] hats. The hats of his friends were then filled. When the hats were soggy and ruined, John took the crowd out and bought them all new hats.

John was said to have “invaded” Philadelphia. He bought a special train which traveled across the Pennsylvania Railroad. The service which John purchased ran for free for anyone who wanted to travel along with John. Upon his arrival in Philadelphia, John rented the entire Continental Hotel for the day, which cost around $25,000. Of course, a crowd of people trailed behind John and spent a luxurious day with the big spender, gratis.

Early into John’s experience with exorbitant wealth, a man by the name of William Whickam asked to buy his farm for $1.2 million dollars. Mr. Whickam payed $30,000 upfront for a preliminary six month lease, plus an additional $5,000 each month thereafter for six months. This initial payment was enough to convince John that he was

well on his way to being a true baron of the oil industry. He continued to spend.

John financed a minstrel show, attempted a career as a boxer, also attempted a career as a theater patron, also also attempted a career as a race horse owner, and, when he believed he was destined for stardom, bought a cornet (however, after numerous complaints due to daily practices from neighbors in the hotel which he lived, John gave up his coronet playing dreams).

The New York Times wrote that Coal Oil Johnny “set records for scattering coin along great white ways that have never been surpassed. [...] He set out to squander the [oil] gains in every form of wild excess.”

Penniless Vagabond

Coal Oil Johnny’s life of luxury quickly came to an end in 1865. William Whickam backed out of their million dollar deal. At the same time, John began to hear from creditors who wanted their money back. None of his friends turned up to follow him anymore.

Lawsuits were filed against John when he couldn’t come up with the $65,000 he owed to numerous creditors, corporations, and individuals. Too ashamed to face his wife, Eleanor, and son in Venango County, John began traveling from city to city in an attempt to find work. He landed in Kansas City for a short while where he joined the minstrel group he had once financed.

John and his family settled in Kearney, Nebraska, where John found work with the Burlington Railroad. By all accounts, John became a dependable and good husband and father, and he “refused” to speak of the old Coal Oil Johnny days to anyone – including his family and closest friends. He was said to be sensitive about the events, although he did publish an autobiography in 1902 which claimed that not all of the shenanigans attributed to him were true and were, more often than not, the actions of Seth Slocum and other friends of his from the time, going so far as to saying that his association with Slocum had a “disastrous effect” on his life.

In the end, Coal Oil Johnny didn’t deny his shopping sprees, his illogical purchases, the opulent, custom made carriage, or his heavy indulgence of hard liquor. He also conceded that he could have been enebriated to remember some incidents…

John Washington Steele passed away in 1920 from pneumonia. He was living in Nebraska.

Thanks for reading!

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider supporting the Museum by making a monetary contribution by clicking the button below, so we can continue to provide content for learning and discovery.

.png)

Comments